Campaigning for a Tony Award already involves a nonstop schedule of events, photo opportunities and jostling to best position each show on television broadcasts, in articles and at galas.

That process becomes harder when the show has already closed.

This year, the now-shuttered “Choir Boy,” “The Boys in the Band,” “Torch Song,” “The Waverly Gallery” and “Bernhardt/Hamlet” reaped a collective dozen nominations — including one best play nod and three for best revival of a play, as well as accolades for individual actors.

Without the chance to invite the Tony voters back to the theater, these limited runs have to get creative, using archived footage, actors as roving representatives of the show and increasingly, social media.

And without ticket sales generating income, it’s more difficult to ask investors to spend additional money on promotion, which can total in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and includes the mailing out of scripts and cast albums to the 800-plus Tony voters and helping nominees make the rounds.

Online videos have been somewhat of a game changer in this arena. Barry Grove, the executive producer of Manhattan Theatre Club, said the nonprofit is campaigning for “Ink” (which is still open) and “Choir Boy” by taking out the always crucial New York Times ad for both shows and sending “Choir Boy” scripts to voters. But the theater company is also increasingly relying on videos and social media to promote the shows.

“I wouldn’t say it’s easier, but it is certainly different now,” Grove said. “We’re not just in the world of print ads and brochures anymore.”

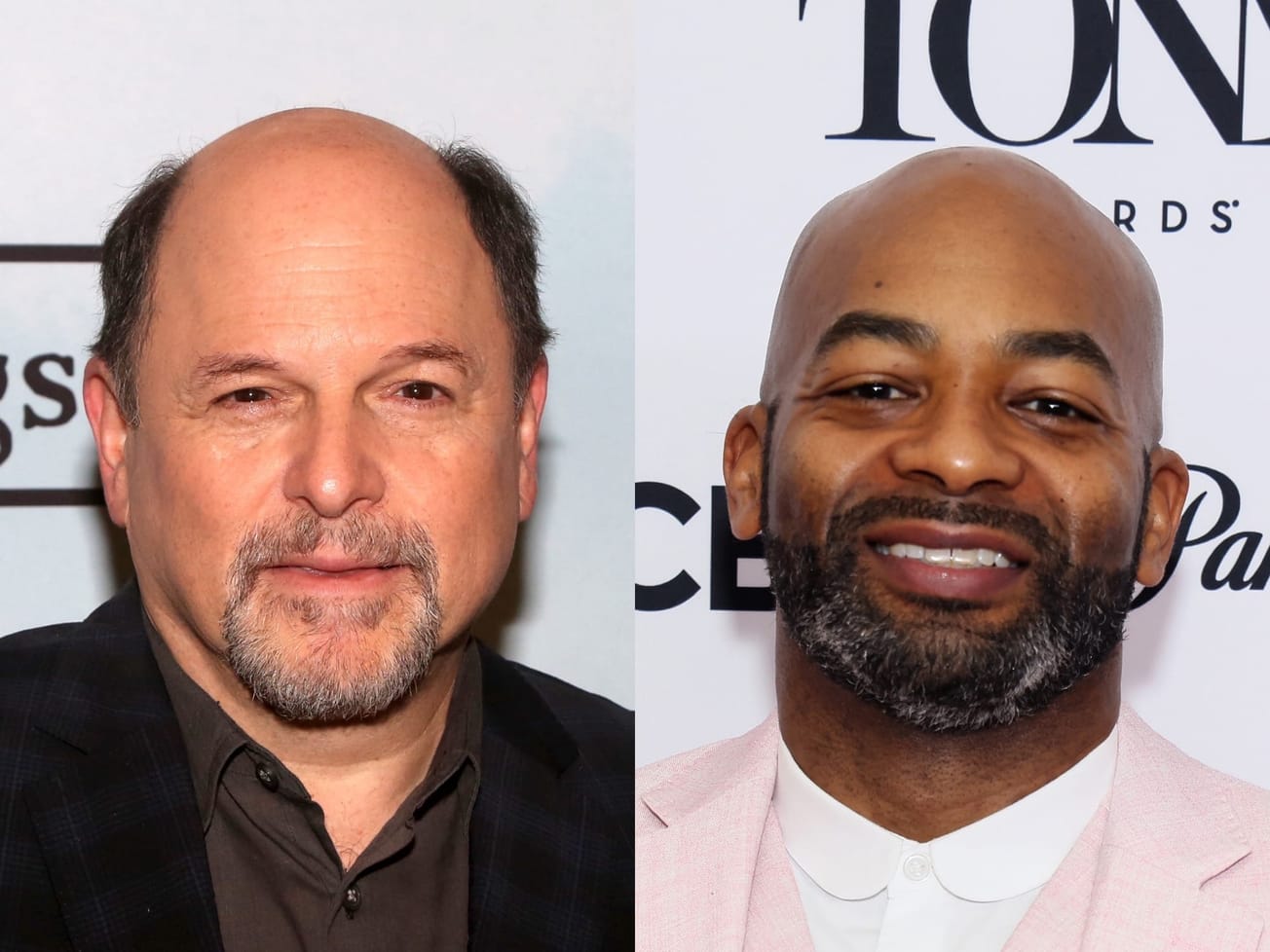

The use of video allows “Choir Boy’s” nominated star Jeremy Pope, who is currently in “Ain’t Too Proud,” and playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney, who is in Chicago working on his next show, to participate in the process. Grove says McCraney created his own “short selfie video” for voters. Additionally, MTC can repurpose videos and other social media material made during the run of the show.

“It’s not the same as being live in the theater but it certainly captures the memory of a show,” Grove says, especially for someone who has already seen the production.

Other closed shows have taken this a step further. When “Falsettos” was nominated for best revival of a musical in 2017, along with four acting nominations, Lincoln Center Theater sent a CD of the original cast recording to voters — standard operating procedure. What was unusual was the fact that the producers also sent an online link to the then-unseen Live from Lincoln Center film of the show and invited all voters to a special screening of the movie version at a Manhattan multiplex. (In the end, “Hello, Dolly!” still won the Tony.)

From the actors’ perspective, those new approaches seem to be creating more of a balance between shows, says Robin de Jesús, who earned his third acting nomination for “The Boys in the Band” — a limited run that ended last summer and that was nominated in the revival category, alongside de Jesús’s nomination.

“I think the unwritten rules about shows that are closed getting hurt in the voting are shifting or being thrown out,” he said.

But, as Toni-Leslie James, who is nominated for best costume design for “Bernhardt/Hamlet,” says, the experience of seeing the nominated elements live can’t be beat.

“There’s nothing like being in the theater, watching people move in the clothing, seeing the costumes with the actors, the set and the lighting,” James said. “You cannot replicate the experience of live theater.”

And campaigning for best musical, the biggest Tony Award in terms of box office impact and one that helps show tour and license future productions, in particular, is difficult without being able to woo the out-of-town producers and theater owners at the Broadway League Spring Road conference.

“It’s a huge disadvantage for certain awards, especially best musical,” said Oliver Roth, whose company OHenry Productions is a producer on the Tony-nominated “Burn This.” “Winning won’t help ticket sales, which is a big part of some voters calculations for best musical. And, if you weren’t able to make it to the Tonys, it’s hard to say you were the best of the year.”

Since 1949, the first year of the best musical Tony Award, only 28 closed musicals have been nominated. Of those, the only show that has managed to win best musical after closing was “Hallelujah, Baby!” a 1968 tuner that ran for close to 300 performances.

New plays and play revivals, however, are viewed somewhat differently, as the runs are often purposely limited, either because they exist as one part of a season at a nonprofit theater, or in order to attract stars.

For example, in recent memory, “Jitney” won the 2017 Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play after closing as did “A View From the Bridge” the previous year.

Campaigning, whether it be for an open or closed show, is a delicate subject: producer Scott Rudin, of “The Waverly Gallery,” would not comment, nor would Roundabout Theatre Company, which produced “Bernhardt/Hamlet,” or the producers of “Torch Song.”

The traditional process — facilitated, in come cases, by producers who hold onto money for a spring campaign — continues to include getting the nominees to New York and keeping the individual, and thus the show, front and center.

This process can be facilitated by producers of the closed show, as was the case when Julie White, nominated this year for “Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus,” won a best actress Tony for “The Little Dog Laughed” in 2007, months after the show had closed.

“The producers were helpful, and our press rep definitely helped coordinate the when, where and why for my appearances,” she said.

De Jesús, who says he feels like he is appearing not only for himself, but as a representative for his show, says he has been choosing which events to attend on his own. His friends who are producers on other shows urged him to get a press agent for the campaign, but he declined.

“This is where artistry meets capitalism, and it’s very necessary, but the campaigning feels a little icky for me,” he said. He added that the events, however, are not all about competition and provide a welcome opportunity to socialize with the other nominees.

To that end, there are advantages to the actors campaigning with a closed show.

Compared to the “The Little Dog Laughed” campaign, White says her current experience of doing eight shows a week (including the day of the awards), is “stressful and exhausting” — she spent one recent Monday, her day off, presenting at the Obies with co-star Kristine Nielsen and then sitting on a panel with her other co-star, Nathan Lane, at the 92nd Street Y.

“When your show is closed, it’s just a celebration,” she says. “At all these events you say, ‘Yes I will have another drink. And an extra helping of dessert.’”