Jez Butterworth did not set out to write “The Ferryman.”

Rather, as is the case with many of his plays, inspiration took hold and would not let go until a cast of more than 20, live animals and a real baby appeared on the page.

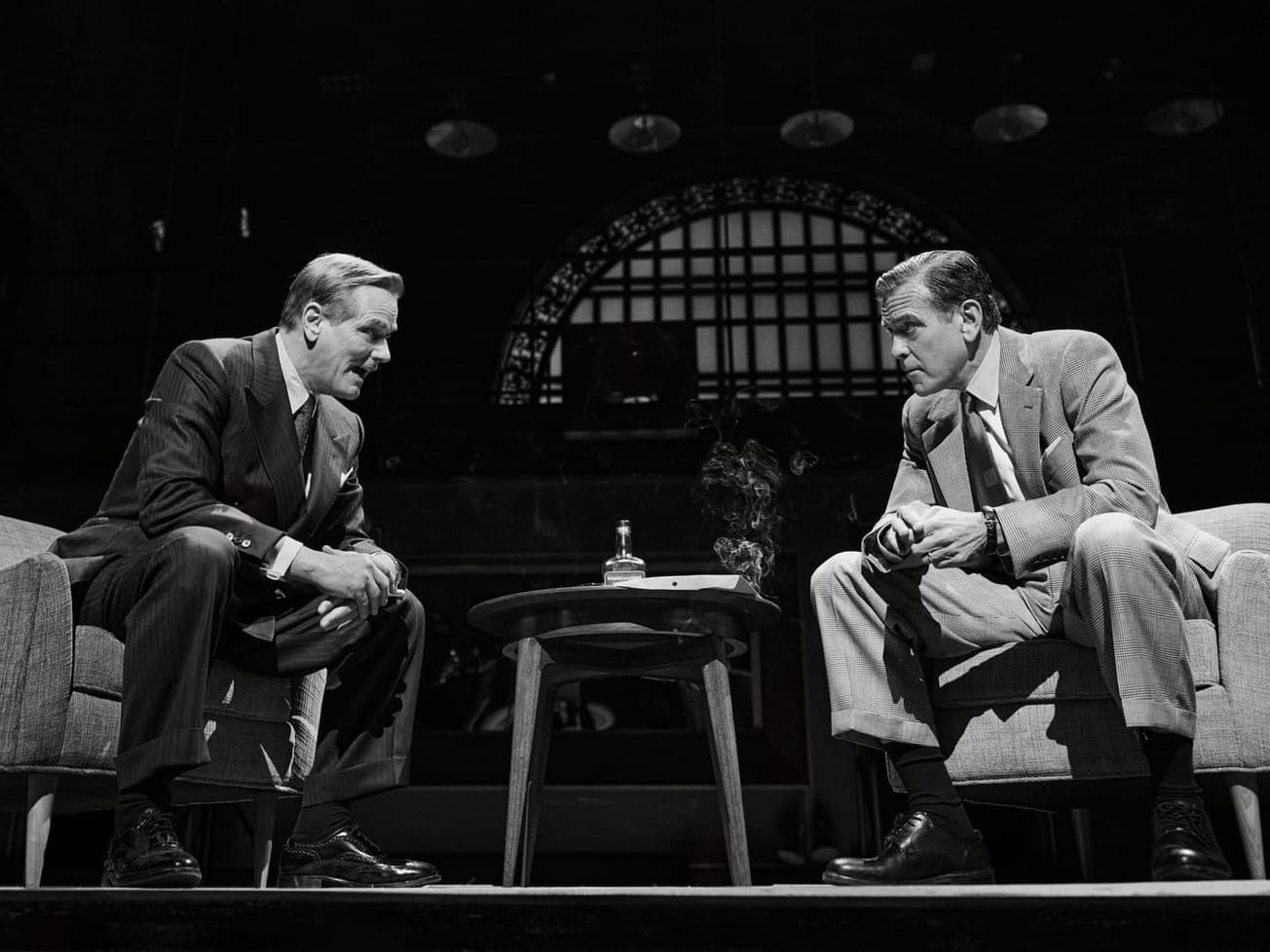

After opening at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre this fall, the play was nominated for nine Tony Awards, including Best Play and a Best Actress in a Leading Role nomination for Laura Donnelly.

Butterworth, who also penned “Jerusalem” and “The River,” and his partner, Donnelly, who originated the role of Caitlin Carney on the West End and on Broadway, spoke with Broadway News about how the play came to be and the permanence of well-crafted theater.

Edited excerpts:

Broadway News: Where did the idea for the “The Ferryman” start?

Laura Donnelly: My uncle was one of a group of about 16 people in Northern Ireland known as “the disappeared,” and he was murdered and secretly buried by the IRA in 1981. His body was discovered three years later. And there were a group of people who suffered the same treatment, only most of their families had to wait decades for them to be discovered. So we got to discussing that one night, and it was something that Jez found incredibly inspirational.

Jez Butterworth: I don’t know why it is. I’ve not written many plays over the years, but when I do, it’s something that really grips hold of me, and I can’t really explain, even afterwards, why that subject rather than another one did that. This subject was one that I would have not touched with a barge pole, being English. I had no natural appetite to go wading into the politics of Northern Ireland or even into somebody whose family history is close to me. There were so many reasons not to do it. And so the fact that it happened anyway is kind of despite my conscious efforts.

BN: How did you decide that you wanted such a large and vibrant family to be on stage?

Butterworth: When I have an idea for a play, it starts to build, and there’s a moment where it’s like the doorbell rings and there’s either three people standing there or there’s 33 people standing there. It’s not really a conscious choice, they just kept coming out of the woodwork.

I don’t know much about theater production, but I know enough about it that it’s expensive every time someone walks on the stage, and yet I couldn’t stop them. It was like a tap I couldn’t switch off. Thankfully when it came time to doing the show at the Royal Court, the producer, Sonia Friedman, didn’t say, “Can we have half as many kids?” She went with it.

BN: And when did the live animals and the baby come into that picture?

Butterworth: Again it was just like they were at the door. I’m as surprised as you are. It just feels that you’re just writing down something you’re getting told.

BN: Did the play change at all when it transferred from London to Broadway? Were there any changes to the script?

Donnelly: Two words.

Butterworth: What were the words?

Donnelly: You changed Spar to shop, because Spar is a name of a store in Ireland, and it kept getting mistaken for “the spa” here. So people thought that we were talking about prostitutes, instead of a store. And the other word was cigarettes instead of Woodbine because, again, Woodbine is a brand. So it was literally just getting rid of those two, and a few cast members changed.

Butterworth [jokingly]: I’ll change anything just to have any audience. Change it, it doesn’t matter.

Donnelly: You changed two words. And it’s not like you said Target.

BN: What do you hope that audiences are taking away from this?

Donnelly: I think the best you can hope for with any audience is that they go away feeling a little bit more connected to themselves and to the people in their lives. That they have just a richer sense of their own experience and their humanity. And they go away thinking. I think if we leave people thinking, then it sat with them, and I think that’s the most we can ask.

Butterworth: When I’ve gone to see my favorite plays, the ones that haunt me, sometimes for decades, it feels like such a gift. I remember going to see “The Weir” by Conor McPherson, and even saying its name now gives me goose bumps because of the experience that I had when I went to see it. The idea that there’s that kind of treasure available in the theater, along with a lot of hundred-to-one shots that you wish you’d never attended, but the idea that there is that kind of an experience there, I marvel at it because I don’t get that way with film. There’s something about the presence of actually being there as the narrative unfolds, in the room with Richard III, rather than reading about him or seeing him on the TV, that I think, does something, when it’s done well, to an audience which is permanent.