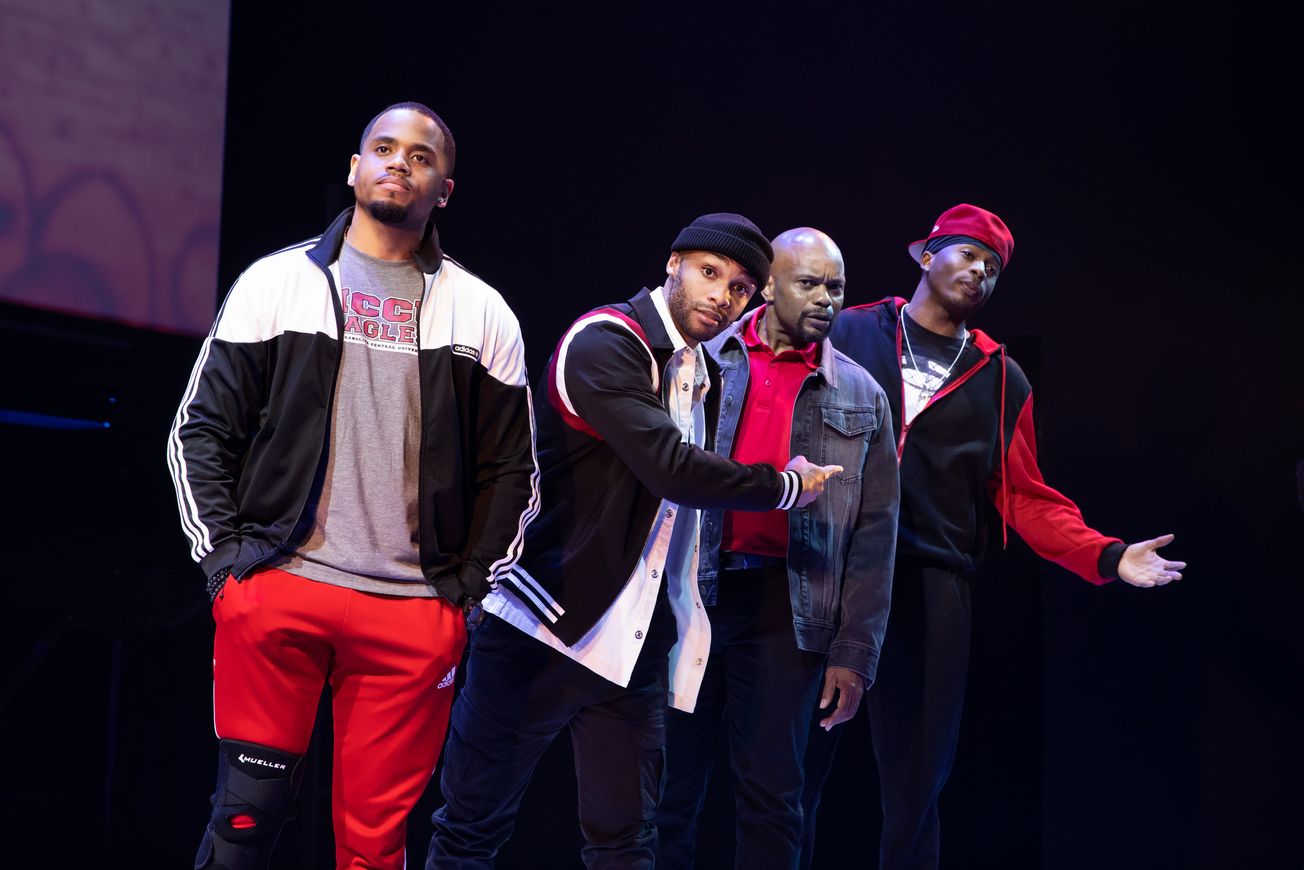

The busy streets of Brooklyn provide the background to Keenan Scott II’s “Thoughts of a Colored Man,” but firmly seizing the foreground are the seven captivating actors who bring to life the dreams, fears, memories, hopes and, yes, all-encompassing thoughts of Black men, both archetypal and piercingly specific, as they move through a single fall day. Written in a mixture of styles — monologues and dialogues, rhymed poetry, song and traditional staged dramatic scenes — the play, at the Golden Theatre, serves up a kaleidoscopic if occasionally didactic portrait of Black men’s lives as they are lived today in the city.

Review: ‘Thoughts of a Colored Man’ asks the audience to listen

The busy streets of Brooklyn provide the background to Keenan Scott II’s “Thoughts of a Colored Man,” but firmly seizing the foreground are the seven captivating actors who bring to life the dreams, fears, memories, hopes and, yes, all-encompassing thoughts of Black men, both archetypal and pierc...