Deciding which Disney property to bring to Broadway is a two-part process: there’s a brief, discerning look at the company’s empire, and then gut instinct takes over.

“Alan Menken says to make musicals you have to think with two brains,” said Thomas Schumacher, president and producer at Disney Theatrical Productions, as he points to his head and then to his stomach. “And I would say that that’s the closest description I’ve ever heard to what it takes. And then you add a collaborator.”

In the last 25 years, Disney Theatrical Productions has staged 10 shows on Broadway, alongside productions on the West End and on the road. Each project has followed its own unique path as ideas have flowed through different divisions of the Walt Disney Company.

Take “Aida.” Schumacher was originally priming it to be an animated feature from Disney Animation until Elton John said he’d like to work on a stage musical. With “Frozen,” Schumacher simply saw an internal, unfinished screening of the film and thought, “This is a musical.”

Disney Theatrical’s upcoming musical adaptation of “The Princess Bride” came to the company via Alan Horn, chairman of the Walt Disney Studios, who was involved in the making of the 1987 film. Disney has now exclusively revealed that the musical will feature a score written by “The Band’s Visit’s” and “The Full Monty’s” David Yazbek and a book co-written by “Jersey Boys” writer Rick Elice and Bob Martin, who penned the book for “The Drowsy Chaperone.”

Ultimately, each of these projects was chosen for the theater because Schumacher and his team believed the stage could elevate the story and that, in turn, the project would enrich the Disney Theatrical resume.

A film’s popularity does play a role in whether a title comes to Broadway. But critically, it must also have a great score and, in Schumacher’s words, “ask to be a stage enterprise.” The latter part is somewhat subjective, largely depending on whether Schumacher or a creative team member see a way in to the project. (“Someone else will come, and they will be able to figure out how ‘Toy Story’ goes on stage or ‘Monsters, Inc.’ I don’t see it,” he said.)

There are other factors to consider, too.

For example, stories that primarily focus on a character traveling from location to location generally don’t translate well to the stage. Instead, Disney Theatrical looks for resonant themes and moments that can be expanded and heightened.

“There’s a certain sense not of epicness, but either moral conundrums and moral high ground that can be taken, something thematic that is rich,” Schumacher said. “And something that calls for the best of what stage can do, as opposed to just putting the movie on stage.”

When bringing an existing Disney property to stage, the first thing Menken — who has translated his music from three Disney animated films to Broadway — looks at is how to restructure it as a two-act show, figuring out where the act break occurs and where to place the emotional tentpoles. He also needs to balance the inclusion of favorite moments from the film with the desire to bring new dramatic elements to the stage.

This often leads to rearranging the score, typically by adding spoken words or dialogue, or by moving songs to different points in the story.

“You want it to feel like the same experience, but it is in fact an experience where every second of it has been reexamined and adapted,” Menken said.

Not all Disney films with music are inherently musicals. Schumacher sees “Mary Poppins” as a film with music; “Aladdin” was more of an action film.

“It really wasn’t a musical, it was an action-adventure picture,” Schumacher said of “Aladdin.” “But when Alan Menken and Chad Beguelin began to write it, they turned it into not only a musical, but sort of a Genie Follies. That, to me, makes it a piece of theater.”

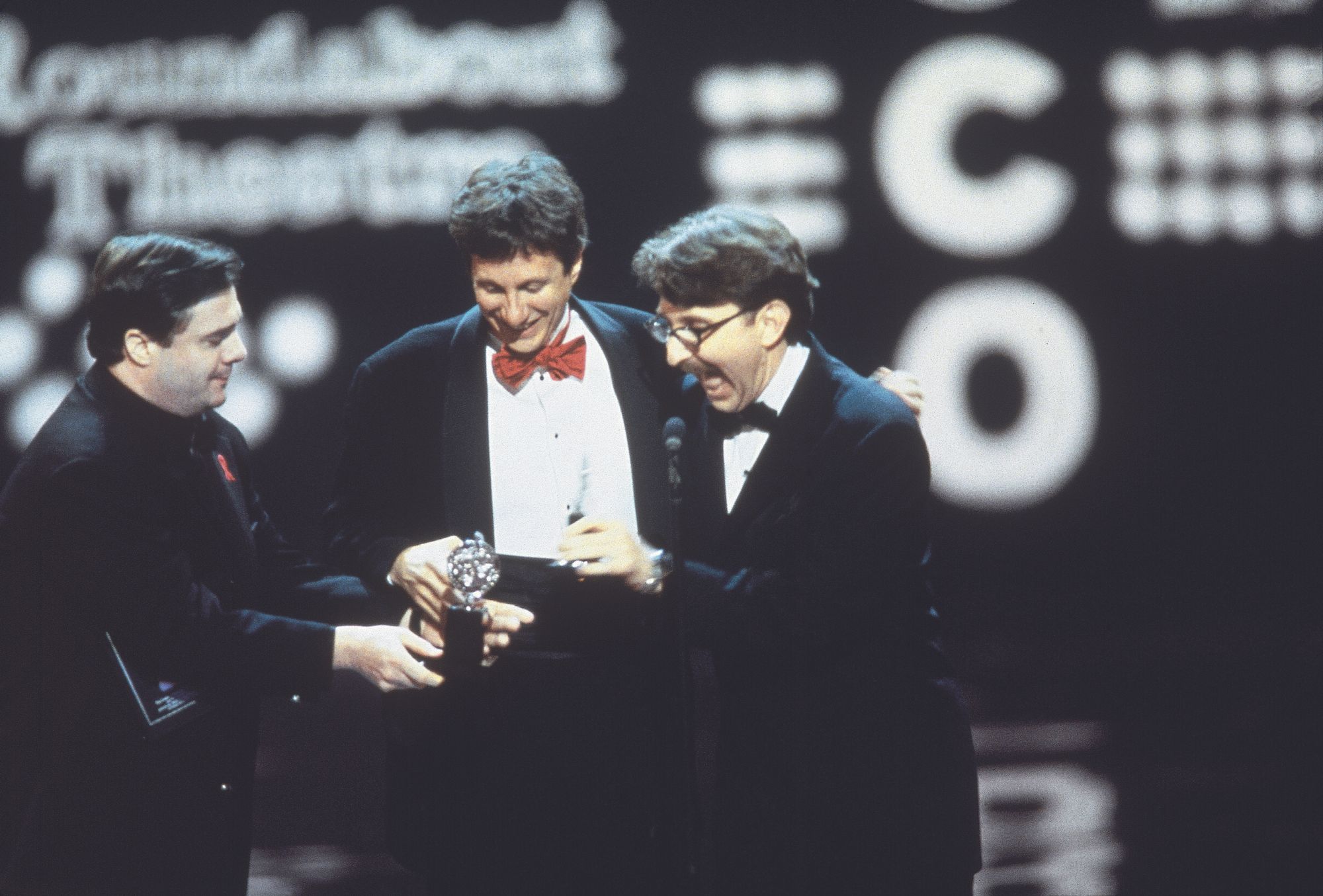

“Beauty and the Beast,” on the other hand, appeared ready-made for the stage. It was chosen as the first-ever Disney property to come to Broadway in part because then–New York Times critic Frank Rich called the 1991 film score the “best Broadway musical score” of the year.

‘Can your friends do this? Can your friends do that?’

When brainstorming ideas for stage productions, Schumacher said he runs them past Horn and Robert Iger, chairman and chief executive of the Walt Disney Company. He might also reach out to other divisions of the company to see if his plans conflict with theirs.

“We all have access to each other’s stuff, but for the most part, the people who make things inside the company, at least the old-school people, we all know each other,” Schumacher said.

That group now includes Jennifer Lee, chief creative officer of Walt Disney Animation Studios, who already speaks regularly with Schumacher, a former president of Animation, about her team’s projects. Schumacher also gives notes on early screenings of animated films.

Having worked on a Broadway musical — Lee wrote the book for the musical adaptation of “Frozen” after writing and co-directing the film — she says she can now spot the upcoming projects in the animated catalog that she feels could be adapted for the stage. She shares her ideas with Schumacher.

“We certainly fantasize about it, and there are some things that we’re working on where I say, ‘Oh, God, if he could see that,’” Lee said.

Now that Disney has completed its acquisition of 21st Century Fox, including film and television assets, the company’s theatrical arm may have access to a wider array of titles — though the exact divisions of intellectual property for Broadway still remain unclear.

“Disney Theatrical looks forward to evaluating the opportunities and new business this acquisition might present,” a Disney spokesperson said.

In some cases, Disney owns all the rights to a property, but in others, the company may only own a portion of the rights, as was the case with “Mary Poppins.” (The musical followed a circuitous path to Broadway after an initial impasse between Disney, which owned the score and the underlying story, and stage rights holder Cameron Mackintosh, who said he obtained those rights in 1993 after convincing author Pamela Travers that he wanted to create a new version of her books for the stage. In the end, both parties realized they had a similar vision.)

Within the Disney empire, there has to be a consideration of brand equity as titles are spread out across international productions, national and international tours, what’s playing at theme parks, upcoming films and Disney Channel programming.

The goal is to prevent the properties from cannibalizing each other, sapping audience numbers and ultimately diluting the value of the titles. And as Disney Theatrical exists as one part of Walt Disney, there are the shareholders of the close-to-$200-billion company to consider.

To that end, Disney Theatrical produces relatively few plays — “Peter and the Starcatcher” came to Broadway in 2012 while “Shakespeare in Love” opened on the West End two years later — because of the economics.

“When your business is not just about one production, but about taking the productions around, doing multiple, multiple productions, plays don’t lean into that so much,” Schumacher said. However, he added that the box office success of “To Kill a Mockingbird” might change that mindset.

Of the nine Broadway musicals solely produced by Disney, six have recouped, according to Disney, with “Frozen” close to reaching that milestone, too.

Schumacher said that Disney is currently maxed out with three titles on Broadway — “Frozen,” “Aladdin” and “The Lion King.” On a few occasions, the company has had four shows running at once, but Schumacher said that oversaturated the market.

All of this is laid out in Disney Theatrical’s five-year plan, which currently includes 21 productions playing around the world, five of which are in the U.S.

There is something there that wasn’t there before.

There was no formal theatrical division of the company when Disney brought “Beauty and the Beast” to Broadway in 1994. The initiative was spearheaded by Michael Eisner, then chairman and chief executive of the Walt Disney Company. Schumacher came on to the theatrical side with “The Lion King” after executive-producing the film.

“We were running animation at the same time which was a very important, big business,” Schumacher said. “And so it was like a side thing. And then it became something.”

The shift toward being a full-fledged business, which now employs about 140 people in New York alone, came after Disney picked up momentum on Broadway with the still-running “Lion King,” then “Aida,” before beginning to license shows.

With its wealth of resources and popular titles, Disney’s entrance to Broadway led to the transformation of Times Square and the ailing New Amsterdam Theatre. The company also managed to lower the average age of the Broadway theatergoer as families began returning to the theater, according to Michael Riedel, author of theater history book “Razzle Dazzle” and its upcoming sequel.

“They helped put Broadway back into the mainstream of American popular culture, particularly with the show ‘The Lion King,’” Riedel said.

Efforts to reimagine Disney properties for the stage have not always been well-received by critics, though Riedel notes that “The Lion King,” funneled through the vision of director Julie Taymor, gives him hope for titles to come. And, he adds, Disney has the resources to continue taking risks.

That is, while Disney Theatrical needs to make thoughtful decisions, with the larger company in mind, the undertaking of new musicals ultimately requires everyone to want to work on that next project.

“It takes so much passion for everybody in this place, all of us have to be so committed to the idea and we have to work in lockstep,” Schumacher said.